When I went through medical school, nutrition education was, at best, an afterthought. To be honest, many of us probably relied on what our parents taught us about healthy eating. We were taught the basics: eat more fruit and vegetables, consume less fat and sugar, and stay hydrated. Fibre was mentioned briefly, lumped into a single category mainly to do with bowel habits and colon cancer. We were taught to instruct our patients to eat more bran and Metamucil. My personal health journey taught me much later to appreciate fibre’s profound role in overall health. Here’s what I’ve learned.

Common Myths About Fibre

- “Fibre is only for constipation.”

- While fibre helps with constipation, its benefits extend far beyond digestive health, including heart health, blood sugar control, and weight management.

- “All fibre is the same.”

- The distinction between soluble and insoluble fibre is critical because they have different functions and benefits.

- “You can only get fibre from fruits and vegetables.”

- Whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds are excellent sources, and in many cases better sources of fibre than fruits and vegetables. Not all plants are equal when it comes to fibre.

Understanding the Different Types of Dietary Fibre?

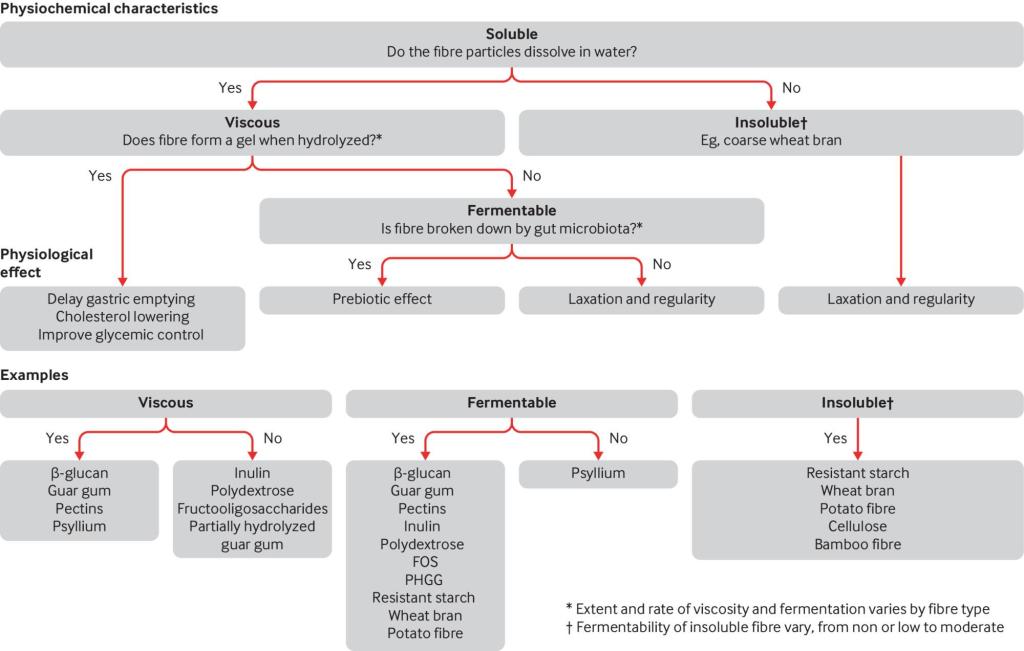

Until recently, I didn’t realise how complex and essential fibre is in our diet. I used to think it was just one simple nutrient found in plant-based foods. Nonetheless, dietary fibre varies widely in its source, type, quality, and effects on the body—something food labels and recommendations don’t always reflect. Adding to the confusion, synthetic or isolated fibres can be included in foods and drinks under different names. What I’ve learned is that there are several types of fibre, each offering unique health benefits. While all added fibres count toward the “recommended daily intake,” their benefits depend on their properties. These properties include how soluble, viscous, or fermentable they are.

Figure extracted from McKeown 2020

- Soluble Fibre: Soluble fibre dissolves in water, forming a gel-like substance that helps regulate blood sugar and lower cholesterol levels. Good sources include:

- Grains – oats and barley

- Legumes – lentils, black beans, and chickpeas are also good sources

- Fruit like – apples, oranges, and berries

- Vegetables – carrots and Brussels sprouts

- Seeds – chia seeds and flaxseeds.

- Insoluble Fibre (aka “roughage”): Insoluble fibre promotes healthy digestion by adding bulk to stool and supporting regular bowel movements. Good sources include:

- Whole grains – whole wheat, brown rice, and quinoa.

- Vegetables – broccoli, cauliflower, and green beans

- Skins of fruits and vegetables – apples, pears, and potatoes.

- Fermentable Fibre (aka “prebiotics”): Fermentable fibre is a type of soluble fibre. Gut bacteria can break it down and produce beneficial compounds like short-chain fatty acids. These support digestive and metabolic health. Fermentable fibres like inulin, pectin, and resistant starch are found in many foods. Good sources include:

- Grains – oats, barley

- Legumes – lentils, chickpeas, and black beans.

- Fruits – bananas, apples

- Vegetables – onions, garlic, asparagus

- Most nuts

The Health Benefits of Fibre

1. Supports Digestive Health

Fibre is probably best known for its role in promoting regular bowel movements and preventing constipation. Insoluble fibre adds bulk to stool. This makes it easier to pass. Soluble fibre can help with diarrhea by absorbing excess water.

- Observational studies: A systematic review found that dietary fibre intake reduces the risk of developing diverticular disease. This is a common condition affecting the colon linked to constipation. (Aune 2020).

2. Lowers Cholesterol Levels

Soluble fibre binds to cholesterol in the digestive system, helping to remove it from the body. This process can lower LDL (“bad”) cholesterol levels, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

- Observational studies: A meta-analysis in The Lancet found that higher dietary fibre were significantly associated with reduced risk of mortality. This intake significantly lowered the risk of mortality. They were also linked to a reduction in numerous chronic diseases. The study recommended increasing dietary fibre intake to at least 25–29 g per day. It found additional benefits at higher intakes. Most interestingly, dietary fibre and whole grain content were more reliable indicators of carbohydrate quality. This was in comparison to dietary glycemic index (“GI”). (Reynolds 2019)

3. Helps Regulate Blood Sugar

Soluble fibre slows the absorption of sugar, which can help prevent blood sugar spikes and improve overall glycemic control. This is particularly beneficial for individuals with diabetes or those at risk of developing the condition.

- Intervention studies: A randomised trial published in the The New England Journal of Medicine demonstrated important findings. A diet high in dietary fibre, particularly soluble fibre, exceeding the levels recommended by the American Diabetes Association (ADA), significantly enhanced glycemic control. It also reduced hyperinsulinemia and lowered plasma lipid levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes. This helps manage blood sugar and improves overall metabolic health (Chandalia 2000)

4. Promotes Healthy Weight Management

Research consistently shows that higher dietary fibre intake is linked to lower body weight and a reduced risk of obesity. Observational studies have found an inverse relationship between fibre consumption and body mass index (BMI). Intervention studies indicate that adding fibre to the diet can decrease food intake. It can also promote weight loss. These effects are believed to result from fibre’s ability to enhance satiety by slowing digestion and influencing gut hormones.

- Observational Studies: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies reported that individuals with higher dietary fibre intake had a significantly lower risk of developing obesity. (Veronese 2018)

- Intervention Studies: Clinical trials have demonstrated that increasing fibre consumption leads to reduced energy intake and weight loss, likely due to enhanced feelings of fullness and delayed gastric emptying. (Jovanovski 2020)

- Mechanisms of Action: Fibre’s impact on satiety is mediated through the modulation of gut hormones such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), which play roles in appetite regulation. (Bakarat 2024)

5. Feeds Your Gut Microbiome

Dietary fibre is made up of plant-based carbohydrates that our bodies can’t break down using human digestive enzymes. Instead, certain bacteria known as ‘fibre fermenters‘ in our gut process this fibre through fermentation. They produce beneficial substances called short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) as the main result. SCFAs (e.g. butyrate), regulate key metabolic processes by activating specific receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. These processes include glucose and lipid metabolism as well as satiety regulation, which are critical factors in the development of obesity and metabolic syndrome

Certain types of soluble fibre, known as prebiotics, serve as food for beneficial gut bacteria. These bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that supports gut health, improves glucose and lipid metabolism, satiety regulation (feeling full) and reduces inflammation in the body.

- Evidence: Studies have demonstrated the role of fibre in enhancing gut microbiome diversity and promoting SCFA production. (Cronin 2021)

How Much Fibre Do You Need?

- In the US, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 recommends that adults eat 28 to 34 grams of fibre each day (depending on sex)

- In the UK, the NHS Eatwell Guide recommends 30 grams of fibre each day. Despite these guidelines, most people consume much less than the recommended amount.

How do you achieve 30 grams of fibre per day?

Here’s an example:

- Breakfast: 10g (3.5g soluble, 6.5g insoluble)

- Oatmeal (1 cup): 4g total fibre (1.5g soluble, 2.5g insoluble)

- Chia seeds (1 tbsp): 4g total fibre (1g soluble, 3g insoluble)

- Blueberries (1/2 cup): 2g total fibre (1g soluble, 1g insoluble)

- Mid-Morning Snack: 5g (1.4g soluble, 3.6g insoluble)

- Apple with skin (1 medium): 4g total fibre (1.2g soluble, 2.8g insoluble)

- Almonds (10): 1g total fibre (0.2g soluble, 0.8g insoluble)

- Lunch: 11g (4g soluble, 7g insoluble)

- Lentil soup (1 cup): 8g total fibre (3g soluble, 5g insoluble)

- Whole-grain bread (1 slice): 3g total fibre (1g soluble, 2g insoluble)

- Afternoon Snack: 3g (1.1g soluble, 1.9g insoluble)

- Carrot (1 medium): 2g total fibre (0.5g soluble, 1.5g insoluble)

- Hummus (2 tbsp): 1g total fibre (0.6g soluble, 0.4g insoluble)

- Dinner: 11g (3.4g soluble, 7.6g insoluble)

- Cooked quinoa (1 cup): 5g total fibre (1.2g soluble, 3.8g insoluble)

- Roasted Brussels sprouts (1 cup): 4g total fibre (1.5g soluble, 2.5g insoluble)

- Sweet potato (1/2 cup): 2g total fibre (0.7g soluble, 1.3g insoluble)

- Grand Total: 30g total fibre (13.4g soluble, 16.6g insoluble

A Personal Reflection

I wish medical school had delved deeper into the nuances of nutrition. Looking back, I particularly wish it had covered the profound impact of fibre on health. I have changed how I approach my meal planning. I also offer better advice to others because I understand different types of fibre and their unique benefits. I was stunned. Some simple tweaks, like adding beans to my meals, made a huge impact on my cholesterol. They also improved my glucose profile and overall wellbeing. This knowledge is something I now prioritize sharing—with my family, my friends, and now, through this blog, with you.

Recipe Inspiration

If you’re looking for an idea to start your fiber-fueled journey, check out this Chana Dhal with Eggplant Curry recipe. You can find it on my Instagram @Wengs_Culinary_Adventures. It’s full of plant diversity, nutrient dense, incredibly tasty and comforting. The recipe is big enough to have leftovers that freeze well so its great for meal prepping.

Chana dal is a split desi chickpea. It’s smaller than regular chickpeas but just as hard. I recommend soaking them for at least an hour (or overnight) to reduce cooking time. If you’re too lazy to soak, you can either pressure cook it, or substitute it with red lentils. Pair it with wholegrains (e.g barley) instead of rice, or scoop it up with toasted multi-grain bread. Throw in a handful of baby spinach while it’s still hot. If you’re a Malaysian like me, this goes perfectly with a roti canai or paratha.

The original recipe is by @NyonyaCooking. I converted her stove top recipe to cook in the Thermomix. I chose not to add potatoes to thicken the dish. Instead, I blended the chana dhal to reach my desired consistency.

Let’s start adding more fibre to our lives, one meal at a time! I would love to hear how you fibre-charge your meals.

Stay tuned for my next post. I’ll dive deeper into the fascinating world of soluble fiber. It’s a little-known nutrient that plays a crucial role in delivering many of the health benefits we often hear about!

References

- McKeown, N. M., Fahey, G. C., Jr, Slavin, J., & van der Kamp, J. W. (2022). Fibre intake for optimal health: how can healthcare professionals support people to reach dietary recommendations?. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 378, e054370. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2020-054370

- Aune, D., Sen, A., Norat, T., & Riboli, E. (2020). Dietary fibre intake and the risk of diverticular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. European journal of nutrition, 59(2), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-01967-w

- Reynolds, A., Mann, J., Cummings, J., Winter, N., Mete, E., & Te Morenga, L. (2019). Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet (London, England), 393(10170), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9

- Chandalia, M., Garg, A., Lutjohann, D., von Bergmann, K., Grundy, S. M., & Brinkley, L. J. (2000). Beneficial effects of high dietary fiber intake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The New England journal of medicine, 342(19), 1392–1398. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005113421903

- Veronese, N., Solmi, M., Caruso, M. G., Giannelli, G., Osella, A. R., Evangelou, E., Maggi, S., Fontana, L., Stubbs, B., & Tzoulaki, I. (2018). Dietary fiber and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 107(3), 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx082

- Jovanovski, E., Mazhar, N., Komishon, A., Khayyat, R., Li, D., Blanco Mejia, S., Khan, T., L Jenkins, A., Smircic-Duvnjak, L., L Sievenpiper, J., & Vuksan, V. (2020). Can dietary viscous fiber affect body weight independently of an energy-restrictive diet? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 111(2), 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz292

- Barakat, G. M., Ramadan, W., Assi, G., & Khoury, N. B. E. (2024). Satiety: a gut-brain-relationship. The journal of physiological sciences : JPS, 74(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12576-024-00904-9

- Cronin, P., Joyce, S. A., O’Toole, P. W., & O’Connor, E. M. (2021). Dietary Fibre Modulates the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients, 13(5), 1655. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051655

Leave a reply to reallyfull6bf38db0fa Cancel reply